Of all the illustrators alive today, there has been one man whose work has been a constant fixture throughout my life. I was one of those strange girls that would rather be outside excavating dinosaur bones in my backyard, getting my hands and knees dirty, than inside with a dollhouse. I spent countless hours pretending to be a world-famous archeologist, discovering hidden temples and pretending I had stumbled upon portals to other worlds. My favorite book reflected this: Dinotopia by James Gurney. I poured over those books, taped print-outs of his paintings on my wall, and I still have my first copy of The World Beneath on the bookshelf – now with the spine taped together because of the many times that book accompanied me into the woods. When I graduated high school, as my gift, my parents drove me hours away to a tiny museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin where James Gurney’s Dinotopia paintings were on display. They are even more incredible in person. My favorite painting? The Black Fish Tavern from The World Beneath. The use of light and detail in that painting is incredible and I remember walking around the last corner of that gallery and there it was, sitting on an easel as you walked out the door.

Of all the illustrators alive today, there has been one man whose work has been a constant fixture throughout my life. I was one of those strange girls that would rather be outside excavating dinosaur bones in my backyard, getting my hands and knees dirty, than inside with a dollhouse. I spent countless hours pretending to be a world-famous archeologist, discovering hidden temples and pretending I had stumbled upon portals to other worlds. My favorite book reflected this: Dinotopia by James Gurney. I poured over those books, taped print-outs of his paintings on my wall, and I still have my first copy of The World Beneath on the bookshelf – now with the spine taped together because of the many times that book accompanied me into the woods. When I graduated high school, as my gift, my parents drove me hours away to a tiny museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin where James Gurney’s Dinotopia paintings were on display. They are even more incredible in person. My favorite painting? The Black Fish Tavern from The World Beneath. The use of light and detail in that painting is incredible and I remember walking around the last corner of that gallery and there it was, sitting on an easel as you walked out the door.

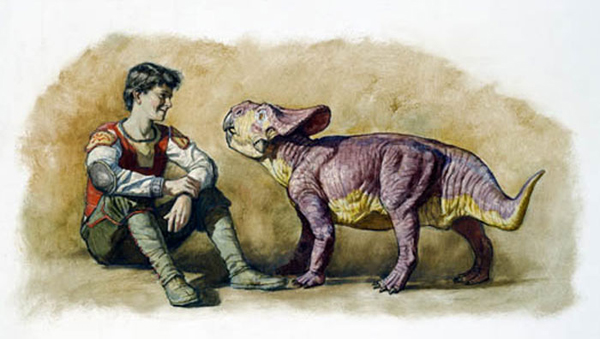

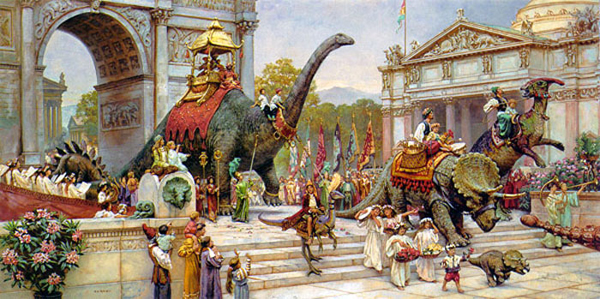

For those who don’t know him, James Gurney is a writer and illustrator, best known for Dinotopia and his work for National Geographic Magazine. “He specializes in painting realistic images of scenes that can’t be photographed, from dinosaurs to ancient civilizations.” In fact, one of my favorite art guide books is Imaginative Realism: How to Paint What Doesn’t Exist, an excellent book for anyone interested in fantasy illustration. You can learn much more about James Gurney and his work by visiting his website, which was recently redesigned by his talented son, Dan. Check it out and take a look at his gallery. Thank you again to James for this fantastic interview. Enjoy!

On with the Dinosaurs! …I mean Interview!

As a kid, dinosaurs played a huge role in my everyday imaginary adventures. How were you first introduced to dinosaurs and the different civilizations that make appearances in Dinotopia and when did they begin to appear in your sketchbooks?

I was bitten by the dinosaur bug as a kid, thanks to the Zdenek Burian illustrations in the Time/Life book on evolution and a few trips to natural history museums. I was also fascinated by lost civilizations. I grew up with a bound set of old National Geographics outside my bedroom door. I’d tiptoe out in the hall at night to read about great explorers like Hiram Bingham discovering Machu Picchu. My ambition in third grade was to find a dinosaur or a lost city. I started excavations in my backyard and had my friends helping me until their mothers told them they couldn’t come over anymore because they always came home with their pockets full of dirt.

I majored in archaeology at UC Berkeley, and then worked for many years as an illustrator for National Geographic. They put me in an early grave, you might say, by sending me on assignment to Etruscan Italy to poke around some recently discovered tombs in Tarquinia. They also sent me to Rome, Athens, and Jerusalem, and I worked with a lot of archaeologists and paleontologists. Around 1988 in my spare time I started doing big paintings of lost empires and I came up with the idea of drawing a map of an island and telling about it through the journal of a Victorian explorer named Arthur Denison.

Does your artistic process differ when you’re working on paintings for your fictional books in comparison with work for instructional art books or commissioned pieces?

Not really. Both my Dinotopia paintings and my scientific illustrations are imaginative work, meaning there’s no photo to copy. The idea is to do a realistic painting of something that isn’t visible in front of me. For both science and fantasy paintings, I have to do lots of sketches, and maybe pose models or build maquettes. If it’s a commissioned illustration, I might have to resolve the sketches a bit more than I would if I was doing a Dinotopia painting. The artistic process does differ of course for my plein air work, where I work on oil primed panels, drawing the subject directly with a brush.

In your experience, what was more beneficial in helping you grow as an artist: formal art education or your personal travels and learning on your own?

For me the most beneficial thing was learning on my own and traveling, simply because most art schools weren’t teaching the good stuff 30 years ago. You had to dig it out from the old art instruction books that were 50 or 100 years old. Doing that felt like having Norman Rockwell or Harold Speed or Andrew Loomis as your teacher. Many art schools are better now, and are offering a good skill-based foundation. Still, I’m a real believer in learning through direct observation of nature, which means carrying a sketchbook around constantly, and painting outdoors.

Imaginative Realism is a fantastic book, but for those who haven’t read it – how do you go about creating your paintings of creatures that no longer exist? What steps must you take for the creatures to look as real as they do?

I work completely in pencil and oil. My studio is upstairs in my house, and it’s crammed full of art books, maquettes of architecture, old theater costumes, and sculptures of dinosaurs. My method is based on the nineteenth century academic approach: thumbnail sketches in black and white and color, studies or photos from costumed models, plein air sketches, and lots of reference photos filed away in a set of filing cabinets. The really elaborate paintings can take as long as six weeks, but an average painting goes together in about six days. During my lecture tour this fall I’ll be doing presentations at several different art schools and studios in LA and Ohio. People can find out the list on my blog under ‘Upcoming Appearances.’

Your blog is an amazing resource for all sorts of traditional artists. What is the biggest piece of advice you could give to a blossoming illustrator?

Thanks for the compliment. As far as advice, I’d start by saying: don’t worry! Professionals in the business often complain about the headaches of stock art, photo-illustration, lousy contracts, and disappearing clients. There’s no doubt: it’s a tough time right now to make a living as an illustrator. But it has always been a changing business, whether you were working in 1905, 1925, or 1955. In many ways, this is the best time ever to enter the field. We live in a more visual culture than ever, and never before has fantasy and science fiction been so central to our culture.

I’d also recommend balancing imaginative and observational work. Sketch from life and sketch from your head. And don’t worry about developing a style. Just observe nature faithfully when you’re young. The style will come naturally.

We have more resources at our fingertips – tools, references, printing technology – than any of our artistic ancestors ever dreamed of, and there are unlimited opportunities if we can just try to rise to the high ideals and standards that they stood for. Illustration is a proud calling. We should never forget how lucky we are to be able to conjure dreams out of thin air.

And finally… in one word, what “fuels” your illustration?

Probably the same thing that has fueled artists all along – the desire to tell a story, to bring a character to life, to create a doorway into a world that no one had ever imagined before. I’m constantly reminded of the impact that still pictures can have over us. I got a letter last week from a young woman who is an art student in Germany. She said she found her old copy of Dinotopia after it had been misplaced for many years, and she remembered something her father said about it. He told her that it was a magical book, and that every time she opened it up, there would be a new picture hidden somewhere in its pages that she had never seen before.